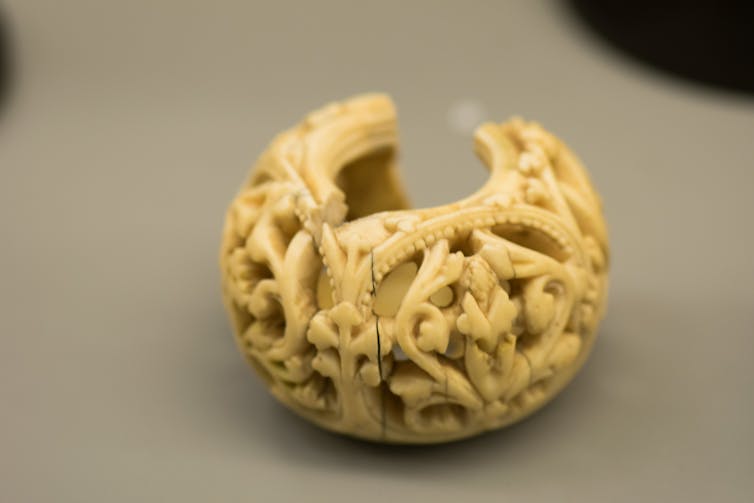

As a substitute for coveted elephant ivory, mammoth tusks can sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars. A rush is underway to dig them out of the frozen earth in Siberia and sell them, mostly to China. The hunt is making millionaires of some men living in this impoverished region — but it’s also illegal.

Photographer Amos Chapple followed a group of tusk hunters in Siberia on assignment for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. He recalled his three-week journey with NPR’s Ailsa Chang.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Interview Highlights

On seeing his first tusk

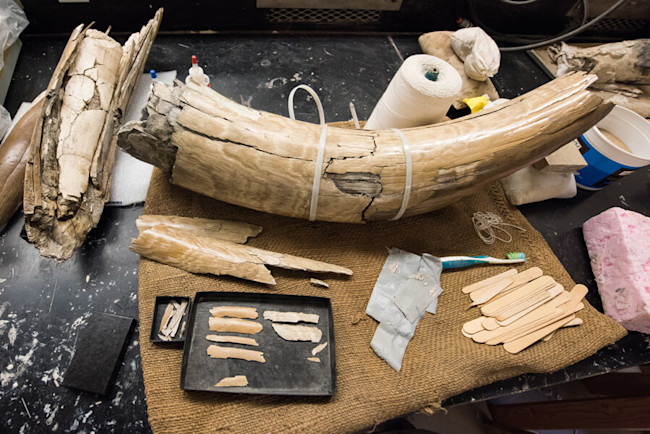

I saw just one beautiful example of a tusk that came out of the ground right in front of me — it was still, like, cold to the touch when it came out. It weighed about [135 pounds] and it was curled. You know, mammoth tusks are very distinctive, because they’re very curly. … They corkscrew a little bit. And you can still smell the animal in them as well.

On how these tusks are excavated

The reason that Siberia is such a mecca for mammoth tusk hunting is because of the permafrost. So there were mammoths everywhere, and they died and their bones sank into the earth, but in most places they rotted because the soil is warm. But once they lock into the permafrost they can just be there almost indefinitely — the bones just don’t decay inside that permafrost.

So you need to carve away that permafrost. And the method that they’ve developed is to get firefighting pumps, and they pull water out of a nearby river, and then they blast away. …

Once they see the end of a tusk, they’ll just give it a little wiggle, and then blast it some more, give it another wiggle, and eventually it’ll come out. It’s like extracting a tooth.

Tusk hunting causes erosion along the edges of the hill.

Amos Chapple/RFE/RL

On what the excavation does to the environment

They would pull water out from the rivers, they’d blast it into the hillside, and those hillsides would effectively melt back into the river. And so the rivers were completely full of silt. It should be one of the most pristine places on Earth, and these guys didn’t even bother taking fishing rods, because the fish were gone.

On the “pretty miserable” hunting conditions

The mosquitoes: that was what made life really, really horrible. … I remember one day I was trying to cross one of these streams when I fell in, and I sat on the bank and I took off one of my gumboots and tried to squeegee out my sock. And the moment I did that, all these black mosquitoes descended on my white, white feet and the contrast was just so superb. …

I took a couple of pictures and then I put my socks back on, and then I limped and whimpered my way towards the river — and I remember thinking I would pay hundreds of dollars right now to be able to plunge my feet into icy, cold water.